Atoms: Fascinating Science of Why Empty Space Feels Solid

One of the most bizarre facts in all of science is that nearly everything you see, touch, or feel, including your body, chair, and the earth beneath your feet, is made of empty space.

Matter, which seems so solid and dependable, is 99.9999999% void. This isn’t poetic exaggeration; it’s a physical reality confirmed by decades of atomic research and quantum theory. At the deepest level, the “stuff” that makes up the universe isn’t really solid at all.

To understand this cosmic joke played by nature, we have to dive into the secret life of atoms, the building blocks of everything, and see how scientists discovered that the foundations of matter are mostly nothing.

The Birth of the Atomic Idea

The notion of atoms is ancient. More than 2,400 years ago, the Greek philosopher Democritus proposed that all matter is made of indivisible particles called atomos, meaning “uncuttable.”

He imagined them as tiny, solid spheres moving through a void. There was no way to test his idea, but it was astonishingly prescient: Democritus had correctly guessed that matter is granular, not continuous.

Unfortunately, his theory competed with Aristotle’s more influential belief that matter was continuous and made of earth, water, air, and fire. For centuries, Aristotle’s view dominated, and atoms remained a philosophical curiosity rather than a scientific reality.

That changed in the early 19th century. John Dalton, an English chemist, revived the atomic idea with experimental evidence. By studying how elements combined in fixed ratios, he deduced that each element must consist of identical atoms, tiny, indestructible units that formed compounds in predictable ways. Dalton’s atoms were solid little spheres, more or less like billiard balls.

At this stage, scientists accepted that atoms existed, but no one had the faintest clue what was inside them.

Cracks in the Billiard Ball: Discovering Subatomic Particles

In 1897, physicist J.J. Thomson made a groundbreaking discovery: the electron. He found that cathode rays, streams of negatively charged particles, were far lighter than atoms, meaning atoms must have internal structure.

Thomson proposed the “plum pudding” model of the atom: a positively charged sphere with electrons embedded inside it like raisins in dough. It was a comforting picture; atoms were still solid, their charges neatly distributed throughout.

But nature had a shock in store.

Rutherford’s Gold Foil Experiment: The Discovery of the Atomic Void

In 1909, Ernest Rutherford, along with Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, performed an experiment, popularly known as Rutherford’s Gold Foil Experiment that would redefine reality.

They fired alpha particles (helium nuclei) at a thin sheet of gold foil, expecting most to pass straight through with slight deflections.

Instead, they found something astonishing: almost every particle went straight through the foil as if the gold were empty space, but a tiny fraction bounced backward, some even directly back toward the source.

Rutherford realized that nearly all an atom’s mass and positive charge must be concentrated in a minuscule core, which he called the nucleus, while the electrons occupied the surrounding volume. The rest, virtually everything, was empty space.

He famously remarked, “It was as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

This was the moment the illusion of solidity began to crumble. The atom, once thought a solid ball, was revealed as a tiny dense center surrounded by vast nothingness.

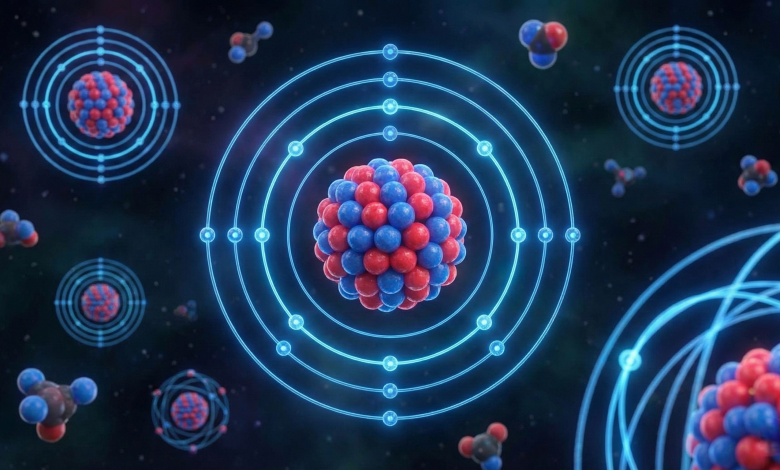

Bohr’s Model: Order in the Atomic Solar System

Rutherford’s discovery solved one mystery but created another: why don’t electrons simply fall into the nucleus under electrostatic attraction?

In 1913, Niels Bohr proposed a solution. He suggested that electrons orbit the nucleus in specific quantized energy levels, like planets circling the sun, but only at certain allowed distances. Electrons could jump between these levels, emitting or absorbing light as they did.

Bohr’s model explained atomic spectra and stabilized the atom. It also kept the nucleus minuscule compared to the overall atom. Even in this model, the atom remained almost completely empty. The nucleus occupied less than a trillionth of its total volume.

Quantum Mechanics and the Electron Cloud

By the 1920s, the picture of the atom underwent another revolution. Physicists Erwin Schrödinger and Werner Heisenberg replaced Bohr’s orbits with quantum mechanics, introducing a probabilistic view of the electron.

Instead of circling in fixed paths, electrons behave like waves, described by a wavefunction that gives the probability of finding them in a particular region. The atom became a cloud of probability, a fuzzy halo of electron presence surrounding a dense nucleus.

The nucleus itself, containing protons and neutrons, is unimaginably small: roughly one hundred thousand times smaller than the atom as a whole. If the atom were the size of a football stadium, the nucleus would be a pea or blueberry at the center, and the electrons would be buzzing near the outer stands. Everything in between would be empty space.

This isn’t a poetic metaphor; it’s a quantitative fact. The atom’s diameter is roughly 0.1 nanometers (10⁻¹⁰ meters), while the nucleus is only about 10⁻¹⁵ meters across. More than 99.9999999% of an atom’s volume is empty.

The Architecture of Emptiness

The nucleus holds more than 99.9% of the atom’s mass, but takes up almost no space. It’s an ultra-dense knot of protons and neutrons, so dense that if you squeezed a teaspoon of nuclear material together, it would weigh billions of tons.

Meanwhile, the electrons, tiny, nearly massless particles, define the atom’s size. Their probability clouds extend far from the nucleus, creating the atom’s apparent volume. But these clouds aren’t solid objects; they are regions where electrons might be found.

So what’s between the nucleus and the electrons? Essentially nothing. A vacuum. A realm filled only by the ghostly presence of electric fields and quantum fluctuations.

If you could remove all that emptiness from every atom in your body, you’d be smaller than a speck of dust, but you’d still weigh the same. In fact, if you removed the empty space from all human bodies on Earth, the entire population could fit inside a sugar cube.

Matter’s apparent solidity is an illusion built from vast emptiness shaped by invisible forces.

Why We Can’t Fall Through the Floor

If atoms are mostly empty, you might ask: why don’t we simply fall through them?

Why does a chair feel solid when you sit?

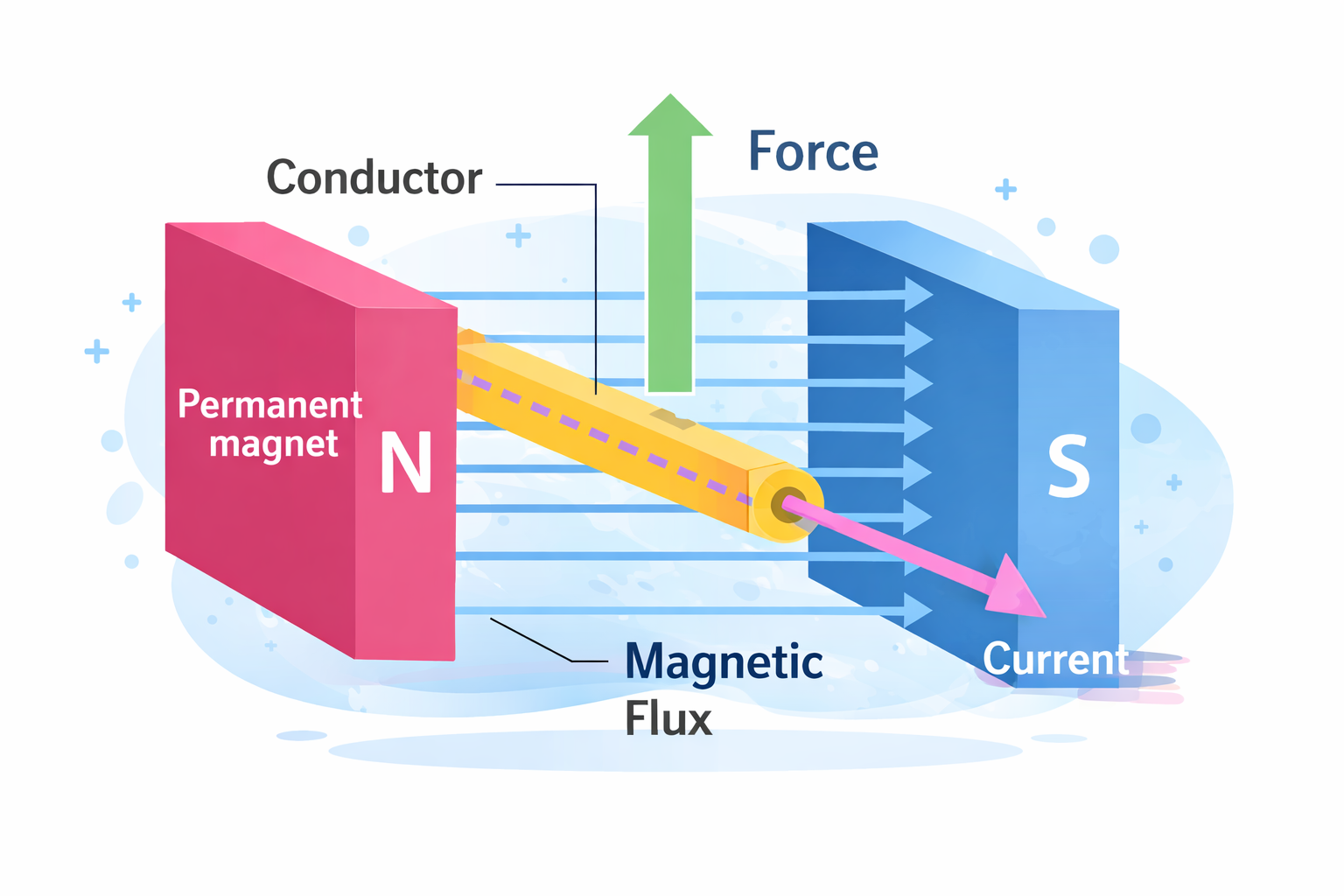

The answer lies in the electromagnetic force and the Pauli exclusion principle.

Electrons carry negative charge, and like charges repel each other. When the electrons in your hand approach those in a table, their electric fields push each other apart. You never actually touch the table; the repulsion keeps your atoms hovering a minuscule distance away.

The Pauli exclusion principle, a rule of quantum mechanics, adds another layer of protection. It states that no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. So when you try to compress matter, electrons resist by occupying higher-energy states, creating an immense counterpressure.

Together, these two principles make matter appear solid, even though its interior is almost completely void. You are, in fact, hovering on a cushion of electromagnetic energy every time you sit, stand, or touch anything.

Seeing the Invisible: How We Know It’s True

Rutherford’s experiment was the first proof of atomic emptiness, but today we have many others.

Electron scattering experiments in the mid-20th century measured the size of the nucleus directly, confirming that it’s about 100,000 times smaller than the atom. X-ray crystallography shows that even in tightly packed solids, atomic centers remain far apart, separated by vast voids on the subatomic scale.

Modern microscopes give us almost tactile evidence. The scanning tunneling microscope (STM), developed in the 1980s, can image individual atoms by detecting the tiny tunneling current that flows when a sharp tip passes near them. The result: crisp arrays of dots, atoms sitting apart with clear gaps between them.

Another device, the atomic force microscope (AFM), “feels” atoms with an ultra-fine needle that bends under atomic forces. These techniques reveal a world where matter is discrete, not continuous. Between those dots and forces lies only space.

Recent breakthroughs have even allowed scientists to image free-floating atoms. In 2025, MIT physicists used optical traps and lasers to photograph individual atoms suspended in vacuum. The very ability to isolate a single atom proves that the spaces between atoms are vast compared to their size.

Every experiment we perform reinforces the same extraordinary truth: atoms are mostly empty space.

Making Sense of Scale: Analogies for the Atomic World

If an atom were the size of a stadium, its nucleus would be a pea at midfield, and the electrons would be buzzing around the outer seats. Everything else, nearly the entire stadium, would be empty.

Or consider this: if you squeezed out all the space in the atoms that make up a person, that person would shrink smaller than a grain of sand, but their mass would remain the same. Compress all humanity the same way, and we’d fit into a sugar cube. That cube, however, would weigh billions of tons.

A neutron star provides a real-world version of this compression. It’s what’s left when a massive star collapses, forcing electrons into protons to make neutrons. In neutron stars, the atomic empty space is gone. A teaspoon of this material weighs as much as a mountain.

Another helpful image is the electric fan analogy. When the fan is off, your hand passes easily through the gaps between blades. When it’s spinning, those same blades fill the circle so completely that the fan feels solid. Atoms behave similarly: the rapid, everywhere-at-once presence of electrons makes the “empty” atom act solid to anything that tries to pass through.

And then there’s a delightful paradox: you have never truly touched anything in your life. Every handshake, every brush against a wall, every keystroke involves electromagnetic repulsion between atoms, not physical contact between particles. When you sit in a chair, you are literally floating, by a distance far smaller than an atom, on an invisible cushion of force.

The Illusion of Solidity

All this leads to a profound realization: what we call “solid matter” is not a continuous substance. It’s a dance of forces and probabilities. Solidity emerges not from the presence of stuff, but from the resistance of fields.

This redefinition has vast implications. It tells us that reality is structured energy, not hard matter. The chair that supports you does so through electron clouds repelling yours; the ground beneath your feet is a field interaction, not a physical barrier.

Understanding this not only explains why we don’t fall through the Earth but also why materials behave as they do. The hardness of diamond, the flexibility of metal, the transparency of glass, all come down to how electron clouds and atomic spacing interact.

Emptiness Across the Universe

This revelation echoes on cosmic scales. Look up at the night sky: the spaces between stars are vast, and even galaxies themselves are mostly void. The pattern repeats at every level, from the microcosm of atoms to the macrocosm of the cosmos.

Matter, it seems, is nature’s decoration on the canvas of nothingness.

Even “empty” space isn’t truly empty. Quantum field theory tells us that the vacuum teems with fluctuating fields and virtual particles, popping in and out of existence. The Higgs field fills space, giving particles mass. Energy is woven into the vacuum itself. The emptiness inside atoms, therefore, is not a barren void; it’s a living sea of quantum activity.

This idea reshapes how we think about existence. The universe, and everything in it, isn’t made of solid building blocks but of energy fields interacting through empty space. Solidity is an illusion, and emptiness is not nothing; it’s the stage upon which everything happens.

What It Means to Be Mostly Empty

There’s something poetic about knowing that you are mostly nothing. It doesn’t diminish human significance; it magnifies the mystery of existence. From this perspective, life itself is a miracle of organization: energy and emptiness arranged into consciousness.

Atoms’ empty interiors make chemistry possible. If they were packed solid, electrons couldn’t move, bonds couldn’t form, and life couldn’t exist. The very “nothing” that seems meaningless is the reason matter behaves in ways that allow complexity.

In a sense, the emptiness within us is what gives us form. It’s not a flaw in nature’s design; it’s the key to it.

The Strangeness of Reality

The idea that matter is mostly empty space is unsettling precisely because it contradicts our senses. We feel weight, pressure, and texture; we hear sound waves bouncing off surfaces; we see light reflecting from solid walls. Yet beneath those sensations lies a ghostly reality, held together by invisible forces and quantum rules.

Science has shown us that the world is not what it seems. The familiar solidity of objects is an emergent property of countless atomic interactions. Each “solid” thing around you is a symphony of forces in a sea of nothing.

Understanding this doesn’t make the world less real; it makes it more wondrous. When you realize that solidity is an illusion sustained by emptiness, every object becomes a marvel of hidden physics. Every atom is a microcosm of mystery.

Conclusion: The Wonder of the Empty Universe

The next time you hold a stone, type on a keyboard, or sip water, remember this: you’re interacting with something that is, at its core, almost entirely empty. Every atom in that object, and in you, is a tiny nucleus surrounded by a vast void, stitched together by electric and quantum forces.

We live in a world built on nothing, yet that “nothing” creates everything we know.

In the secret life of atoms, emptiness and existence are intertwined. Understanding this strange truth doesn’t make the universe less tangible; it reveals just how extraordinary it truly is.

Matter, solidity, touch, all are illusions woven from emptiness. And within that emptiness, the universe found a way to make stars, planets, life, and thought.

That’s the quiet wonder hiding inside everything you see: the solid world you know is a masterpiece of empty space.