The Sky Isn’t Blue: Here’s What Color It Actually Is

The question “Why is the sky blue?” has charmed philosophers, scientists, and curious sky-gazers for millennia.

It seems simple, but the real answer is far more intricate and delightful. In truth, the sky isn’t exactly blue. It’s a canvas of scattered sunlight, shaped by the physics of Earth’s atmosphere and the peculiarities of human perception.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the historical myths, the science of Rayleigh scattering, how our vision processes color, why sunsets are red, what skies look like on other worlds, and what the sky would look like with no atmosphere at all.

By the end, you’ll understand not only why the sky looks blue but also why that answer is a little bit of an illusion.

Ancient Beliefs and Early Theories About the Sky

Before modern science, humans imagined the sky in mystical terms.

Greek philosopher Aristotle believed air might have a faint inherent color visible when observed in large volumes.

Roger Bacon, Kepler, and others extended this logic, suggesting the blue sky arose from the depth of clear air.

Leonardo da Vinci made an important leap. He suggested the sky’s color came from light interacting with small particles in the air, noting that fine smoke under sunlight produced a blue glow. But without knowledge of wave theory, he couldn’t explain why.

Isaac Newton’s prism experiments proved that sunlight contains all visible colors, setting the stage for 18th-century thinkers like Leonhard Euler and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, who even invented the “cyanometer” to measure sky blueness at different altitudes.

Even into the 1800s, many believed the ocean’s reflection caused the sky’s color. But, it’s the other way around. The true explanation came later: Rayleigh scattering.

What Is Rayleigh Scattering?

Sunlight and the Spectrum

Sunlight is composed of all colors of visible light. These colors correspond to different wavelengths: violet and blue are shorter (~400–500 nm), red and orange longer (~600–700 nm).

When this light enters Earth’s atmosphere, it encounters air molecules, primarily nitrogen and oxygen that are much smaller than the wavelength of visible light.

The Scattering Effect

These molecules scatter incoming light in all directions. But they don’t treat all wavelengths equally. Shorter wavelengths, blue and violet, are scattered much more than longer ones.

Mathematically, the intensity of Rayleigh scattering is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the wavelength (1/λ⁴).

This means blue light (~450 nm) is scattered around 8–10 times more than red light (~700 nm). As a result, the sky around us is filled with scattered blue photons coming from every direction.

Think of it like a pinball machine: short-wavelength photons bounce all over, while long-wavelength ones plow straight through.

That’s why, during the day, the sky appears blue but the Sun looks yellow-white-it’s been stripped of much of its blue content.

Why Isn’t the Sky Purple?

Violet light is scattered even more than blue. So why isn’t the sky purple?

- The Sun emits less violet than blue.

- Human eyes are much less sensitive to violet light.

- Some violet light is absorbed by the atmosphere before reaching us.

So, even though violet is physically present, we don’t perceive it as strongly. Our brains blend the scattered spectrum into a dominant blue tone.

Perception: What Your Eyes Are Really Seeing

Human vision relies on three types of cone cells, each sensitive to different ranges of light.

The “blue” cones are tuned to ~430–460 nm, making them poor at detecting true violet (~400 nm).

Add to that the filtering effect of the eye’s lens (which blocks some UV and violet), and the scattered light we actually perceive is predominantly blue.

It’s a reminder that color is not just a property of light-but a collaboration between light and biology.

Sunrise and Sunset: Nature’s Spectacular Filter

As the sun moves toward the horizon, sunlight must pass through much more atmosphere to reach your eyes.

During this long journey, shorter wavelengths (blue and violet) are scattered away, leaving the longer red and orange tones.

As the sun moves toward the horizon, sunlight must pass through much more atmosphere to reach your eyes. During this long journey, shorter wavelengths (blue and violet) are scattered away, leaving the longer red and orange tones.

That’s why sunsets and sunrises feature warm, fiery hues. Pollution, volcanic dust, and humidity can enhance this effect by further scattering and absorbing light. The result? Breathtaking skies that artists and poets adore.

The phenomenon also explains why the Sun itself looks orange or red near the horizon: the blue has been siphoned off.

What If There Were No Atmosphere?

Imagine standing on the Moon. There’s no air, no scattering. The result? A pitch-black sky, even at noon.

Without an atmosphere, sunlight travels in straight lines. You’d see the bright white Sun, but the rest of the sky would be jet black.

Apollo mission photos show astronauts standing in broad daylight with a starless void behind them.

Even on Earth, at high altitudes or in the upper atmosphere, the sky turns darker. The Kármán line (about 100 km up) marks the transition to space. Above it, the sky becomes black.

Skies on Other Worlds: Mars, Venus, Titan, and Beyond

Atmospheres vary wildly across the solar system, producing an array of sky colors.

Mars: Red Days, Blue Sunsets

Mars has a thin CO₂ atmosphere filled with dust. During the day, its sky appears butterscotch or pink-orange. But at sunset, Mars offers a twist: the Sun appears surrounded by a bluish halo.

This happens because Martian dust scatters red light away and allows blue to filter through near the Sun exactly the opposite of Earth.

Venus: Permanent Twilight

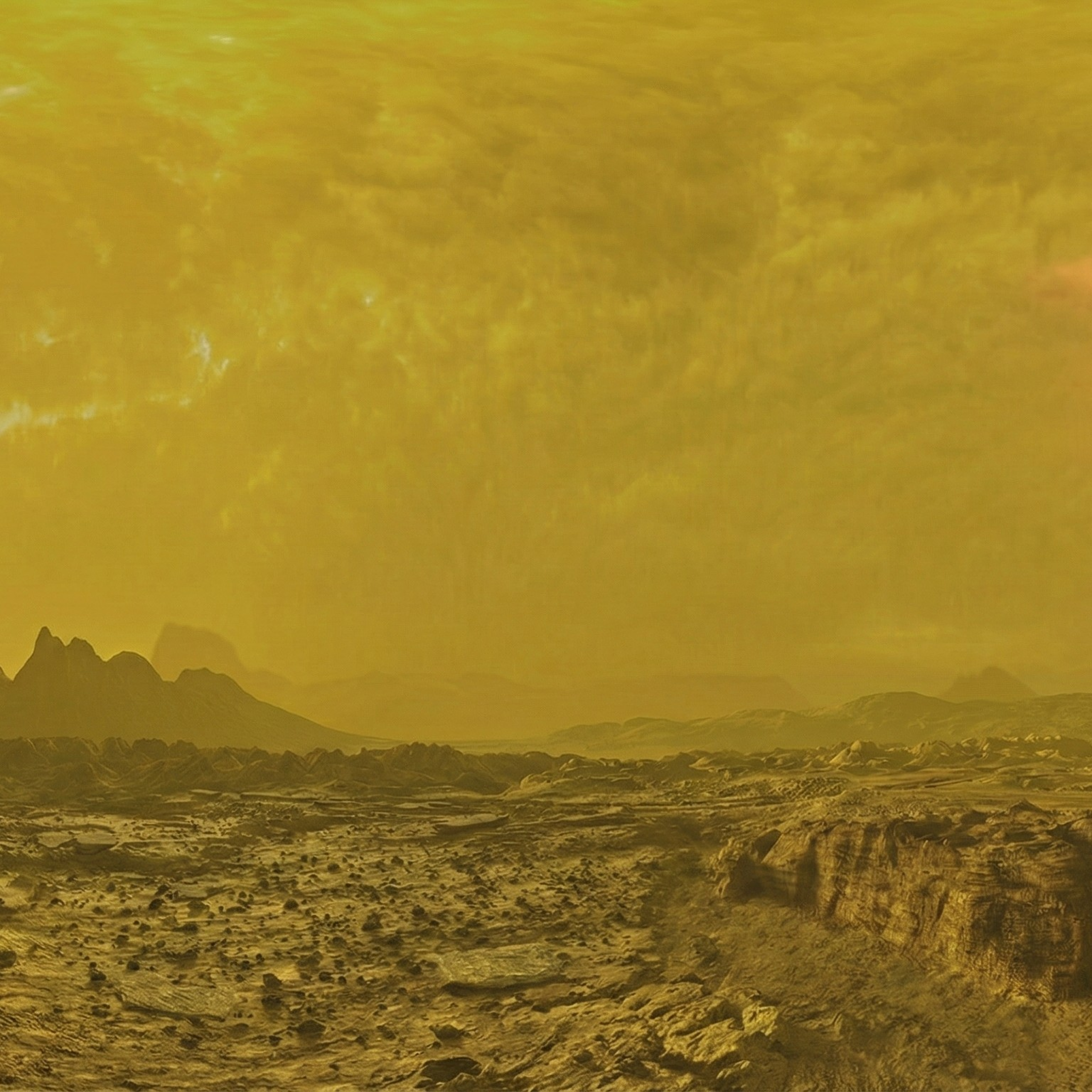

Venus has a dense CO₂ atmosphere with clouds of sulfuric acid. Sunlight barely penetrates.

Photos from Soviet Venera landers show a perpetual orange haze. To a human standing there, the sky would seem dim and yellow-orange.

Titan: Smoggy Orange

Saturn’s moon Titan has a thick nitrogen atmosphere with hydrocarbons that form a permanent orange smog. From the surface, the sky appears dull orange, like a world under sepia-toned streetlamps.

Gas Giants and Ice Worlds

- Jupiter & Saturn: Upper skies may appear pale blue or gray.

- Uranus & Neptune: Methane-rich atmospheres scatter blue and green, giving Neptune a deep blue sky.

Each planet’s unique blend of gases, particles, and sunlight creates a distinctive sky. Earth’s blue is far from universal.

So, What Color Is the Sky Really?

The answer depends on your perspective.

- Physically, the sky emits a spectrum with a peak in violet.

- Perceptually, our eyes interpret the blend as blue.

- Technically, it’s a scattered, unsaturated mix skewed toward blue-violet.

If we had different eyes or if we were on a different planet, we might see the sky as purple, orange, or gray. But here on Earth, under the conditions we evolved with, the sky is beautifully, consistently blue.

Conclusion

The sky’s color is not a property of the air but a dance between sunlight, atmospheric particles, and the peculiarities of human biology. From ancient beliefs to cutting-edge physics, our understanding of the sky has come a long way.

Next time someone asks, “Why is the sky blue?” you’ll know the answer isn’t just about color, it’s about light, air, and how our eyes decode the universe.