The Earth Builders: How Volcanoes Forge New Land

We tend to notice volcanoes as destructive forces – mountains that unmake themselves and erupt with ash and fire.

The news shows us the destruction, and we assume that’s the end of the story.

When we change our perspective from the human time scale to the geologic time scale, we see that the Earth’s surface is not a stage that’s always the same but is always changing.

The earth is a construction site, and the main builders are volcanoes. They are responsible for 80 percent of the surface of our planet and for creating the sea floors that separate and the land masses that connect the continents.

The Magma Engine: Why Some Volcanoes Flow and Others Blow

To better understand why some volcanoes create a paradise like Hawaii and others destroy themselves like Krakatoa, we need to examine the tectonic and magmatic processes that drive such events.

Viscosity as Destiny

The first order of a volcanic event, whether it will be constructive as a flow or destructive as a blast, can be largely determined by the chemical composition of the magma. The critical variable here is silica content.

- The Builders (Mafic Magmas): An example of a magma type is basalt, which has low silica content (45-55%) and is characterised by high temperatures and low viscosity. You can think of basalt magmas like hot sugar syrup. With fewer polymerised molecular structures, magma can flow more, and with this ease of flow, more gas (water vapour, carbon dioxide, and sulphur) can escape as the magma ascends. These eruptions tend to be effusive, producing steady flows that layer upon one another to build vast shield volcanoes, a process clearly visible in Hawaii and Iceland.

- The Destroyers (Felsic Magmas): High-silica magmas (65–75%), like dacite and rhyolite, are cooler and highly viscous. Because of the high silica content, the polymerised network is flow resistant, and it is very “sticky”. Internal pressure mounts catastrophically due to the inability of gas bubbles to escape. When the internal pressure overcomes the strength of the rock, the magma violently fragments into ash and pumice and this process often destroys the volcanic structure instead of adding to it.

Tectonic Real Estate

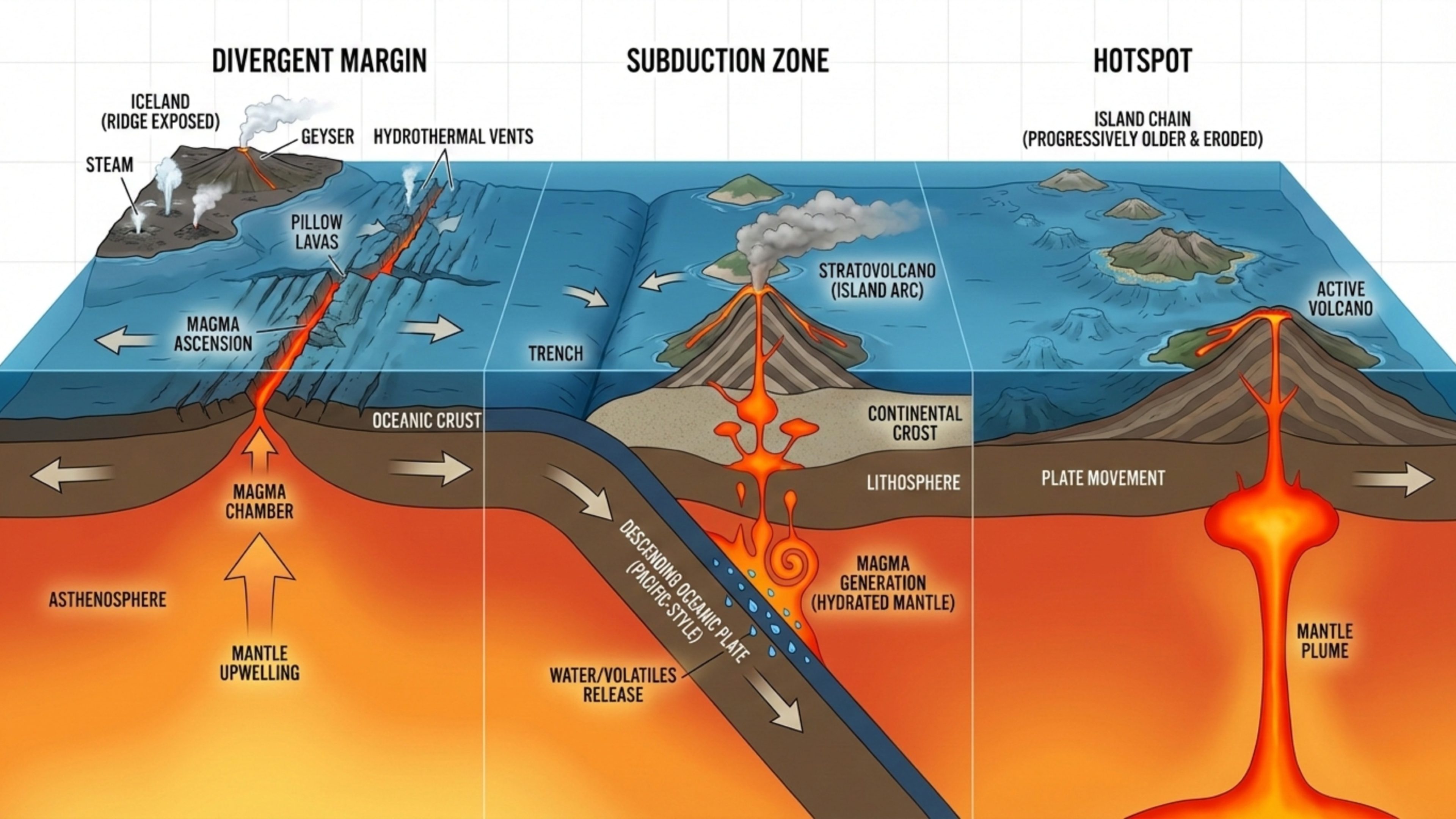

Location is everything. The Earth’s crust is fragmented into tectonic plates, and land formation usually happens at their boundaries:

- Divergent Margins: At mid-ocean ridges where tectonic plates separate, the void is filled by the rising mantle. This process, known as decompression melting, generates basaltic magma which solidifies into a new oceanic crust. This phenomenon is the most productive form of crustal formation on the planet. Iceland is an exceptional example of where such a mid-ocean ridge is exposed above sea level.

- Subduction Zones: When one tectonic plate descends underneath another, like the Pacific Plate going below the Philippine Sea Plate, the subducting slab exudes water into the mantle. It reduces the rock’s melting point, producing magma that ascends to create stratovolcanoes and island arcs, like the ones in the Ring of Fire.

- Hotspots: Some volcanoes develop far from tectonic lineations due to development from a stationary, deep-seated mantle plume, or hotspot, at the core-mantle boundary. As the tectonic plate migrates over the hotspot, it creates a chain of volcanoes.

Birth of an Island: The Pacific and Atlantic Models

Geologically, the formation of a volcanic island is a unique occurrence as it creates a completely new environment, transitioning from submarine to subaerial.

It also reflects an interesting dynamic whereby the island building activity of a volcano is countered by the island destroying activity of the surrounding ocean, as a result of erosion.

The Hawaiian Conveyor Belt

The Hawaiian Islands are well recognized for their contribution to the development of new volcanic land.

The islands also form a part of the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount chain, which is over 6000 km long and forms a chain of undersea volcanoes across the pacific ocean.

The development of the Hawaiian islands is a consequence of the Pacific plate tectonic activity, whereby the Pacific plate moves over a mantle hotspot which is stationary, causing volcanic eruptions.

The plate motion is on a north-west trajectory at a rate of ~8.6 to 9.2 cm annually and during this motion, the plate experiences a large-scale mantle plume which induces eruptions that form large shield volcanoes.

Here, the lifecycle is predictable

- Shield Stage: As the primary stage of land formation, this accounts for more than 95% of the volcano’s total volume. These tholeiitic basalt flows are what sculpt the wide shapes of Mauna Loa and Kilauea.

- Subsidence and Erosion: As the island shifts away from the hotspot, the magma supply decreases, and the islands eventually submerge beneath the waves, becoming seamounts or guyots. The angle in the chain documents a significant change in the motion of the Pacific Plate about 43 million years ago, probably caused by the collision of the Indian subcontinent with Eurasia.

Surtsey: A Real-Time Laboratory

While Hawaii demonstrates to us the long game, the island of Surtsey off the coast of Iceland provided scientists with an island birth real-time laboratory. The eruption started in November 1963 at a depth of 130 meters.

At first, the activity was Surtseyan, an explosive hydromagmatic eruption, caused by the interaction of magma with shallow seawater.

This caused the formation of a tephra cone with loose ash which is very susceptible to wave erosion. Surviving only because the eruption continued long enough to isolate the vent from the sea.

After water could no longer flood the vent, the eruption shifted to the formation of effusive flows of lava, creating a hard basalt armor that was resistant to erosion. This transition is the critical threshold for the permanence of a volcanic island.

Nishinoshima: The Rapid Grower

At the beginning of the 21st century,Nishinoshima of the Ogasawara Arc in Japan showcased the continental crust formation in real time. In 2013, volcanic eruptions began 500 metres southeast of the island.

Unlike most transient volcanic vents, this particular eruption was remarkable for the large quantity of lava produced.

By 2020, the island had combined with the other old islands, increasing the mass of the island to almost 3 square kilometers.

A volcanic eruption’s rheological properties also changed from andesite to become more mafic over time.

This property enables lava flows to thin and laterally to effuse, thus further extending the islands.

This phenomenon shows how marine ecosystems can be converted into terrestrial ecosystems.

India’s Volcanic Heart: From Ancient Traps to Active Seas

While often associated with the stable cratons of the peninsula or the Himalayas, India possesses a significant and active volcanic heritage.

The Deccan Traps: Continental Resurfacing

The scale of land creation at Barren Island or Hawaii pales in comparison to the formation of the Deccan Traps. Occurring approximately 66 million years ago, this Large Igneous Province (LIP) represents one of the most significant volcanic events in Earth’s history.

The eruptions of the Deccan were of flood-basalt, not cone-building. Lava flowed through fissured magma which gushed out, being so fluid that single streams of it spread 1,500 kilometers over the Indian subcontinent.

The mass of lava alone was more than 2,000 meters in the Western Ghats, virtually forming a new vertical landmass on top of the already existing landmass.

It is this volcanic plateau that has come to define the geography and hydrology of the western and central India thus controlling the flow of major rivers such as the Godavari and Krishna.

Barren Island: The Active Factory

India’s current locus of land creation is Barren Island in the Andaman sea. It sits on the active boundary where the Indian Plate subducts obliquely beneath the Burmese Plate.

Barren Island is a classic stratovolcano rising 2,250 meters from the seafloor. After a long dormancy, it has been frequently active since 1991, with confirmed eruptions as recently as late 2025. Recent activity is characterized by Strombolian explosions and transient lava flows that fill the caldera floor and incrementally extend the shoreline. Just to the north lies Narcondam Island, composed of more viscous dacite and andesite, representing the “mature” phase of island arc volcanism.

Hidden Threats: The Crater Seamount

While most of us seldom think of how new land comes into existence, it’s a process that’s slow and spread over decades and often centuries that its often appears invisible to us.

Indian researchers in the year 2023 discovered an active underwater submarine volcano quietly building itself up from the ocean floor near the Nicobar Islands.

This sits about 500 meters below the surface of the sea, the depth at which its presence becomes practically invisible.

But the volcano is active enough for the scientists to detect the gas bubbling up from it and small earthquake clusters around it.

These subtle signs point towards magma moving and volcanic activity that could someday create a new island.

But for now, it remains hidden, growing quietly in the dark underwater areas of the sea that’s seldom visited by humans.

This, although exciting to some, is concerning because unlike volcanoes on land, under sea volcanoes can’t be monitored as easily or effectively.

This could erupt with little warning, pushing enormous volumes of water suddenly with enough force to cause tsunamis.

The threat of a devastrating tsunami is not limited to India but could also impact coastal areas of surrounding areas like Thailand, Indonesia and parts of Myanmar.

This just goes to say how the earth, despite being billions of years old, is still constantly reshaping itself as we scramble to understand.

The Mechanics of Destruction: When Land Vanishes

The thermodynamic forces that build islands can, under specific conditions, annihilate them. “Destruction” is often a catastrophic conversion of solid mass into atmospheric aerosols and submarine debris flows.

Krakatoa 1883: The Caldera Collapse

The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa remains the archetype of volcanic self-destruction. Prior to August 1883, it was a large island; by the end of the month, two-thirds of it was gone.

The destruction was driven by the rapid evacuation of the underlying magma chamber. As cubic kilometers of magma vented, the structural support was removed, and the island collapsed into the void. This collapse generated tsunamis up to 41 meters high.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai 2022: The Magma Hammer

In January 2022, the geological community witnessed an event of unprecedented violence at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai. The volcano had merged two small islands into a single landmass during a constructive phase in 2014-2015.

The 2022 eruption was a “magma hammer” event where magma interacted with seawater at a critical depth. The explosion obliterated the land connection formed years earlier and injected 146 million tons of water vapor into the stratosphere. The atmospheric pressure wave circled the Earth four times, underscoring that the constructive work of a decade can be undone in an afternoon.

Anak Krakatau 2018: Gravitational Instability

Volcanic destruction is not always explosive; sometimes it is gravitational. Anak Krakatau had been growing steadily within the 1883 caldera. However, rapid accumulation of loose material on a steep slope created an unstable structure.

On December 22, 2018, a massive sector of the volcano’s southwest flank collapsed into the sea. This landslide generated a “silent tsunami” that struck coastlines without seismic warning, highlighting the hazard of rapid growth outpacing structural integrity.

Ecological Succession: Life on the Lava

Once the fury subsides, biology takes over. Volcanic landscapes serve as premier natural laboratories for primary succession.

Surtsey: The Isolated Laboratory

Surtsey offers the purest example of primary succession due to its isolation. When the island cooled, it was a biological desert. The first vascular plant, Cakile arctica (Sea Rocket), arrived via ocean currents in 1965.

The ecosystem underwent a regime shift in 1986 with the establishment of a gull colony. The birds acted as biological engineers, importing marine nutrients in the form of guano. This nitrogen injection transformed the soil, allowing lush grassland communities to replace sparse pioneers. By 2004, Atlantic Puffins were nesting on the island.

Mount St. Helens: Biological Legacies

In contrast to Surtsey, the recovery at Mount St. Helens was driven by “biological legacies”—remnants of the old ecosystem.

Because the eruption occurred in May when snowbanks covered the high country, small animals like pocket gophers survived the searing heat. As gophers tunneled through sterile ash to reach food, they brought up nutrient-rich soil from beneath, mixing it with the ash. Simultaneously, nitrogen-fixing lupines colonized the pumice plains, paving the way for conifers to return.

The Gift of the Volcano: Soil and Society

While volcanoes are often viewed through the lens of disaster, their long-term contribution to human civilization is profound.

Andisols: The Basis of High-Density Agriculture

Soils derived from volcanic ejecta are classified as Andisols. Although they cover less than 1% of the Earth’s ice-free land surface, they support a disproportionately large percentage of the human population.

Andisols are defined by the presence of amorphous clays like allophane, which form rapidly from weathering volcanic glass. These minerals possess a high capacity to hold water and organic carbon, making the soil light, fluffy, and resistant to drought—ideal for intensive agriculture.

The Deccan Legacy: Black Cotton Soil

In India, the legacy of the Deccan eruptions is the Black Cotton Soil (Regur). This soil is the product of millions of years of basalt weathering.

Regur soil is rich in montmorillonite clay, which swells when wet and shrinks when dry, creating deep cracks. This natural “self-ploughing” aerates the soil and helps it retain moisture deep within the profile. This characteristic is the foundation of the agricultural economy of Maharashtra and Gujarat, uniquely suiting the land for cotton and sugarcane cultivation.

Planetary Implications: The Climate Thermostat

On geological timescales, volcanism is a primary driver of the Earth’s climate system through the Carbon-Silicate Cycle.

- Volcanic Emission: Volcanoes emit $CO_2$, warming the planet.

- Silicate Weathering: $CO_2$ dissolves in rainwater to form acid, which reacts with fresh volcanic rocks to remove $CO_2$ from the atmosphere.

- Sequestration: The carbon washes into the ocean and is locked away in limestone.

This mechanism likely resolved the “Faint Young Sun Paradox,” keeping Earth warm enough for life billions of years ago when the sun was 30% dimmer than today.

Future Frontiers: Monitoring and Preparedness

As more people settle near volcanoes, drawn by fertile soil, scenic beauty, or simply the pressures of growing populations, the stakes of getting predictions wrong climb higher every year.

The good news is that volcanoes rarely erupt without warning. They grumble first. They swell. They release gases and trigger tremors that, if you’re paying attention, tell a story.

The challenge lies in reading that story accurately and acting on it fast enough.

Modern monitoring has come a long way from the days when scientists would simply watch for smoke.

Today, networks of seismometers pick up the tiny earthquakes that signal magma shifting underground.

GPS stations measure ground deformation with millimeter precision, so when a volcano starts inflating like a slow-motion balloon, we can actually see it happening.

Satellites track thermal anomalies and gas emissions from space, while sensors on the ground sniff for sulfur dioxide and other telltale chemicals leaking through vents.

But technology on its own isn’t enough. The real test comes in translating data into action.

This means having clear evacuation plans in place before a crisis hits, not scrambling to figure things out during one.

It means educating communities so that when officials say “leave now,” people actually leave, and that kind of compliance requires trust built over years, not days.

It means keeping escape routes clear, maintaining emergency shelters, and running drills regularly so that evacuation feels practiced rather than panicked.

Some countries have gotten remarkably good at this. Japan and the Philippines, for example, have developed early warning systems that have saved thousands of lives.

Others still struggle with underfunded monitoring stations and poor communication between scientists and local authorities.

The uncomfortable truth is that we can’t stop eruptions. What we can do is stop pretending they won’t happen.

With enough investment in both technology and community preparedness, living near a volcano doesn’t have to feel like a gamble.

It becomes a calculated risk, one where the odds tilt in humanity’s favor and just a matter of priorities.

Seeing Through the Rock: InSAR

InSAR technology has revolutionized monitoring by using radar waves to measure ground deformation with millimeter precision . at Nishinoshima, where access is dangerous, InSAR allowed scientists to track magma inflation and slope stability from space.

The Challenge of Tsunami Warning

The tragedies of 2018 and 2022 exposed a blind spot: “non-seismic” tsunamis caused by landslides or pressure waves. In response, the Ocean Decade Tsunami Programme is developing an “all-sources” warning system to be operational by 2030.

In the Indian Ocean, monitoring the active Crater Seamount is a priority due to its explosive potential.

The Goal is to Minimise Damage, Not Stop Volcanoes.

The volcano is a paradox of planetary proportions: a destroyer of landscapes and an engine of creation.

From the rapid growth of Nishinoshima to the ancient basalts of the Deccan Traps, volcanism is a story of constant renewal.

The destruction of Krakatoa paved the way for Anak Krakatau; the sterile sands of Surtsey became a thriving ecosystem.

As we advance our monitoring capabilities, our goal is not to tame these forces, but to respect the temporary gift of land they provide.