Rutherford ‘s Experiment: Discovery of the Atomic Void

In 1909, Ernest Rutherford directed one of the most important experiments in the history of science.

The setup was deceptively simple: fire a stream of alpha particles at a thin sheet of gold foil and see where they end up.

What happened next, by Rutherford’s own admission, was “almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

The result overturned the prevailing model of the atom and established something extraordinary: the solid matter we touch, sit on, and are made of is almost entirely empty space.

This was not a minor refinement. It was a conceptual earthquake that shook physics to its foundations and laid the groundwork for nuclear science, quantum mechanics, and our modern understanding of matter.

To appreciate why this experiment mattered, we first need to understand what physicists believed about atoms before 1911.

The World Before the Nucleus

By the early 1900s, scientists knew that atoms were not indivisible, as their Greek-derived name suggested.

J.J. Thomson had discovered the electron in 1897, proving that atoms contained smaller, negatively charged particles.

Since atoms are electrically neutral overall, there had to be an equal amount of positive charge somewhere. But where was it? And what did the inside of an atom actually look like?

Thomson proposed a model in 1904 that was, at the time, perfectly reasonable. He imagined the atom as a sphere of uniformly distributed positive charge, with electrons embedded throughout like raisins in a pudding. The positive charge was spread evenly across the entire volume of the atom, about 10⁻¹⁰ metres in diameter.

This became known as the “plum pudding model,” though Thomson himself never used this analogy; it was coined by a reporter trying to make the idea accessible.

The model made sense given what was known. It explained the atom’s electrical neutrality. It allowed for electrons to be arranged in stable configurations.

And it predicted how particles passing through matter should behave: they would experience small deflections as they passed through the diffuse positive charge, nudged this way and that by countless gentle interactions.

Any deviation from a straight path would be minor, perhaps a degree or two at most.

This is exactly what Rutherford and his colleagues set out to test.

The Rutherford Experiment: Elegant in its Simplicity

Ernest Rutherford arrived at the University of Manchester in 1907, already a Nobel laureate. He had won the prize in Chemistry in 1908 for his work on radioactivity.

At Manchester, he worked with Hans Geiger (later famous for the Geiger counter) and Ernest Marsden, a young undergraduate looking for a research project.

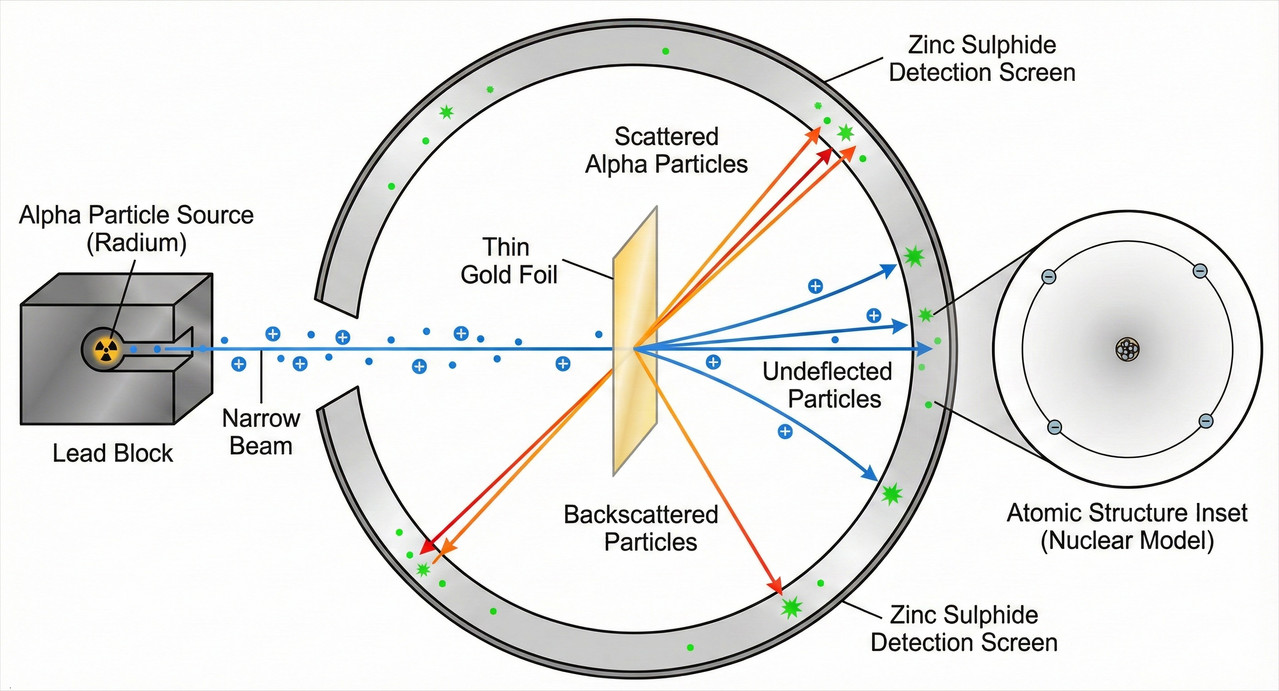

The experiment they designed was straightforward in concept. A radioactive source, typically radium, emitted alpha particles, which are now known to be helium nuclei (two protons and two neutrons bound together).

These alpha particles are relatively heavy and carry a positive charge of +2. They were directed as a narrow beam toward a thin gold foil.

Why gold? Because gold is exceptionally malleable and can be hammered into sheets just a few hundred atoms thick, thin enough that alpha particles could pass through, yet substantial enough to test how matter scattered them.

At about 400 atoms thick, the foil was roughly 10⁻⁶ metres, a thousandth of a millimetre.

Surrounding the foil was a zinc sulphide screen. When an alpha particle struck this screen, it produced a tiny flash of light called a scintillation.

By observing these flashes through a microscope, Geiger and Marsden could determine where the alpha particles ended up after passing through (or bouncing off) the foil.

The work was painstaking. Geiger spent hours in a darkened laboratory, his eyes adapted to the dim conditions, counting individual flashes. They recorded the angles at which particles scattered: how many went straight through, how many deviated slightly, and how many, if any, turned at large angles.

The Astonishing Result

According to Thomson’s plum pudding model, all the alpha particles should have passed through the gold foil with only slight deflections.

The positive charge was supposed to be spread throughout the atom’s volume, so the electric field an alpha particle encountered would be weak and diffuse.

Even passing through 400 atomic layers, the cumulative effect should be minimal.

For the most part, this prediction held. The vast majority of alpha particles passed straight through the foil with little or no deflection. But then came the unexpected observation.

A small number of particles, about 1 in 8,000, deflected at angles greater than 90 degrees. Some came almost straight back toward the source.

This should not have been possible.

Rutherford’s reaction, recounted years later, captured the shock: “It was quite the most incredible event that has ever happened to me in my life. It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

Something in the gold atoms was capable of violently repelling the fast-moving, relatively massive alpha particles. And it was not the diffuse positive charge Thomson had imagined.

What Could Cause Such Deflection?

To understand why this result was so startling, consider the physics involved. For an alpha particle to bounce backward, it must encounter something capable of exerting enormous repulsive force.

The only way a positive charge can repel the positive alpha particle that strongly is if the charge is concentrated into a very small region.

Here’s the key insight: electric field strength depends on charge density. Spread the same amount of charge across a large sphere, and the field at any point is relatively weak. Concentrate it into a tiny volume, and the field near that concentration becomes immensely strong.

Thomson’s model distributed the positive charge across an atom roughly 10⁻¹⁰ metres in diameter.

If instead that charge were packed into a region 10,000 times smaller, about 10⁻¹⁴ metres, the electric field near it would be strong enough to reverse an alpha particle’s direction.

Rutherford spent weeks working out the mathematics. Using classical electrostatics (specifically Coulomb’s law), he calculated the relationship between an alpha particle’s incoming trajectory, its closest approach to the concentrated charge, and the angle at which it would deflect.

The result was what we now call the Rutherford scattering formula, which predicts how the number of scattered particles varies with angle.

The prediction was stark: if the positive charge were concentrated into a tiny nucleus, most particles would pass far from it and deflect very little. Only those on trajectories bringing them close to the nucleus would experience strong deflection. And only those headed almost directly at the nucleus would bounce back.

When Geiger and Marsden tested this prediction systematically in 1913, measuring scattering at different angles with different metals and different foil thicknesses, the results matched Rutherford’s formula with remarkable precision.

The Nuclear Model of the Atom

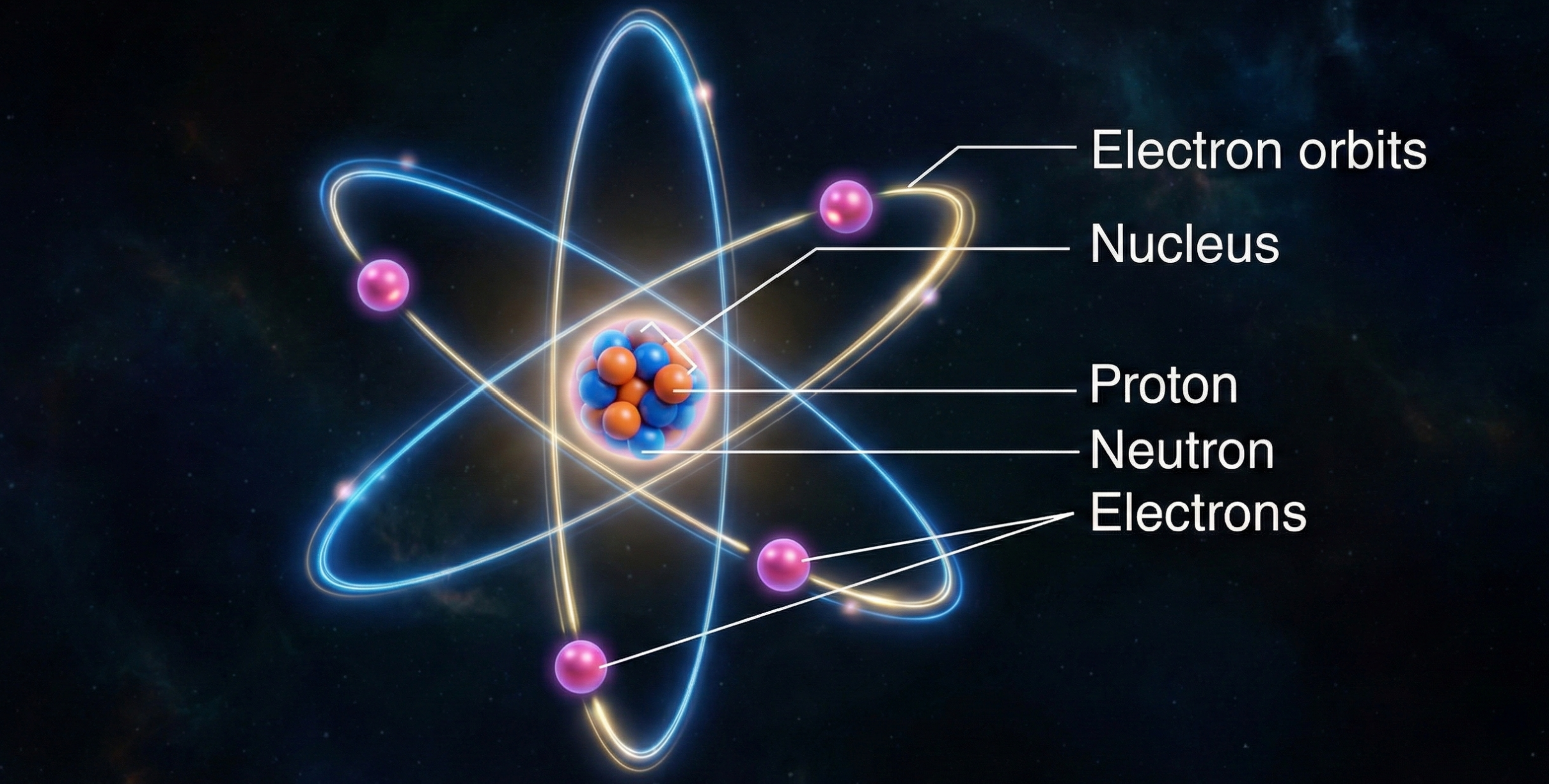

Based on these results, Rutherford proposed a radically new model of atomic structure in 1911. The atom, he argued, consists of:

- A nucleus: an extremely small, dense region at the centre containing nearly all the atom’s mass and all of its positive charge.

- Electrons: negatively charged particles distributed in the space surrounding the nucleus, occupying most of the atom’s volume but contributing negligible mass.

Empty space: the vast majority of the atom’s volume is simply void.

The scale is hard to grasp intuitively. If you enlarged an atom to the size of a football stadium, the nucleus would be about the size of a marble at the centre.

Everything else (the stands, the pitch, the air within) would be the space where electrons might be found, but mostly would be emptiness.

This explains why most alpha particles sailed through the gold foil undeflected. They passed through the empty space between nuclei without coming close enough to any nucleus to be significantly deflected.

Only those rare particles that happened to be on a collision course with a nucleus, or very close to one, experienced the strong repulsion that scattered them at large angles.

The nucleus itself is unimaginably dense. If you could somehow gather a cubic centimetre of pure nuclear matter, it would weigh hundreds of millions of tonnes.

What the Experiment Did Not Explain

Rutherford’s nuclear model was a triumph, but it was also incomplete. It left serious questions unanswered, questions that would drive physics forward for decades.

The most pressing problem was stability. According to classical electromagnetic theory, an electron orbiting a nucleus should continuously radiate energy because accelerating charges emit radiation.

As it radiates, it should spiral inward and crash into the nucleus in a fraction of a second. Calculations suggested this collapse would take less than 10⁻⁸ seconds. Yet atoms are manifestly stable. They persist indefinitely. Why?

Rutherford’s model also said nothing about how electrons were arranged. Were they orbiting like planets around the sun?

If so, what determined their orbits? Why did atoms of each element have distinctive properties and emit light at specific wavelengths?

These questions would be addressed by Niels Bohr, who arrived in Manchester as a postdoctoral researcher shortly after Rutherford’s nuclear model was published.

Bohr introduced quantum ideas to atomic structure, proposing that electrons could only occupy certain allowed orbits and could jump between them by absorbing or emitting light of specific energies.

The Rutherford-Bohr model, as it became known, was a crucial stepping stone toward modern quantum mechanics.

The nucleus itself raised questions too. What kept it together? If it contained multiple positive charges (protons), they should violently repel each other.

Something else must be providing a stronger attractive force. This mystery would not be resolved until the 1930s, when James Chadwick, working in Rutherford’s Cambridge laboratory, discovered the neutron and the strong nuclear force was understood.

Legacy: From Gold Foil to Modern Physics

The gold foil experiment did far more than revise an atomic model. It established a new methodology, using particle scattering to probe matter’s structure, that remains fundamental to physics today.

Every time researchers at CERN collide particles to study their components, they are following a path Rutherford pioneered over a century ago.

The experiment also transformed how we understand everyday matter. The table you lean on feels solid, but it’s mostly empty space.

What you feel is not solid matter touching solid matter; it’s the electromagnetic repulsion between electron clouds that refuse to overlap.

Solidity is an electromagnetic illusion, a force field, in effect, rather than substance.

Rutherford himself went on to achieve the first artificial nuclear transmutation in 1919, bombarding nitrogen with alpha particles and producing oxygen, realising the alchemists’ dream, in a sense, though on an utterly impractical scale.

He mentored a generation of physicists who would shape the twentieth century, including Chadwick, Bohr, and many future Nobel laureates.

The Indian Connection: Nuclear Physics Takes Root

The implications of Rutherford’s discovery rippled across the world, including to the Indian subcontinent, where a generation of brilliant physicists would build on nuclear and atomic science.

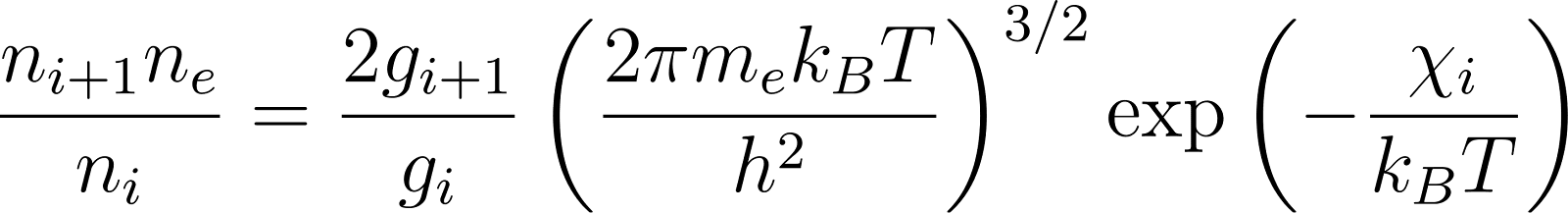

Meghnad Saha, the Indian astrophysicist who developed the thermal ionisation equation in 1920, applied quantum ideas to understand stellar spectra, work that depended fundamentally on understanding atomic structure as Rutherford and Bohr had revealed it.

His equation, which relates a star’s spectral characteristics to its temperature and pressure, remains a cornerstone of astrophysics.

His equation, which relates a star’s spectral characteristics to its temperature and pressure, remains a cornerstone of astrophysics.

The Saha ionisation equation

could not have been conceived without the nuclear model of the atom.

Homi Jehangir Bhabha, another Indian who studied at Cambridge and knew many of the physicists working in this tradition, would later establish India’s atomic energy programme.

His Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and the atomic research centre at Trombay (later renamed Bhabha Atomic Research Centre) were explicitly designed to bring India into the nuclear age.

The research traditions these institutions fostered trace their intellectual lineage directly back to Rutherford’s Manchester laboratory.

The Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics in Kolkata, founded in 1943, carries on this legacy, as do countless research institutions worldwide that study nuclear and particle physics.

Why This Experiment Still Matters

The gold foil experiment is sometimes presented as a curiosity, an elegant historical milestone superseded by quantum mechanics. This undersells its significance.

First, it remains a model of how scientific revolutions happen. Rutherford did not set out to overturn Thomson’s model; he was testing it.

The surprising result emerged from careful observation and was explained by rigorous mathematical analysis.

The new model made specific, testable predictions that subsequent experiments confirmed. This is science working as it should.

Second, the conceptual breakthrough (that matter is mostly void) has never been superseded.

Quantum mechanics refined our understanding of how electrons behave in that void, but it did not restore the atom’s solidity. The emptiness is real.

Third, the scattering method Rutherford developed remains the primary tool for probing subatomic structure.

When physicists discovered quarks in the 1960s, they did so by firing electrons at protons and observing the scattering patterns, exactly the approach Geiger and Marsden used, scaled up enormously.

A Thought Experiment for Everyday Life

Next time you sit in a chair, consider this: the atoms in your body and the atoms in the chair are almost entirely empty space.

What keeps you from falling through is electromagnetic force, the repulsion between electron clouds that won’t interpenetrate.

The chair’s “solidity” is really the strength of electromagnetic fields, not the presence of substance.

In a sense, you are not sitting on matter. You are suspended on a force field, hovering above the void.

This is not mysticism. It is the straightforward consequence of what Rutherford discovered when he fired particles at a thin sheet of gold and some of them bounced back.

The atoms that make up everything we touch, see, and are made of are vast arenas of emptiness with a pinpoint of concentrated matter at their centres.

That discovery, made in a basement laboratory in Manchester over a century ago, reshaped our understanding of what matter is, and by extension, what we are.

The gold foil experiment teaches us to trust evidence over expectation. Rutherford expected the particles to pass through. They mostly did. But the few that didn’t – changed everything.